About The Work: Poetic Visual Stories

My eyes are always searching and yet, the lifting, fluttering flight of the butterfly across time and memory eludes me.

Closer to nature in their daily lives, human cultures of the past had an intuitive understanding of their unity with all of earth’s organisms. My work is inspired by the interconnectedness of our biological lives to all of nature. I have placed my works into four categories, Ecofeminism, Fauna, Flora and Sea. In each of these classifications are works with our human bodies intertwined with natural forms and also abstract forms from the natural world. In the era of climate warming, rising oceans, biodiversity extinctions and existing oppression of women, my intention is to create visually poetic narratives that highlight and honor our being embedded within the natural world.

In 1907 French philosopher Henri Bergson hypothesized in his book, Creative Evolution, of an “elan vital,” or “vital impetus,” which linked the evolution of organisms to consciousness.

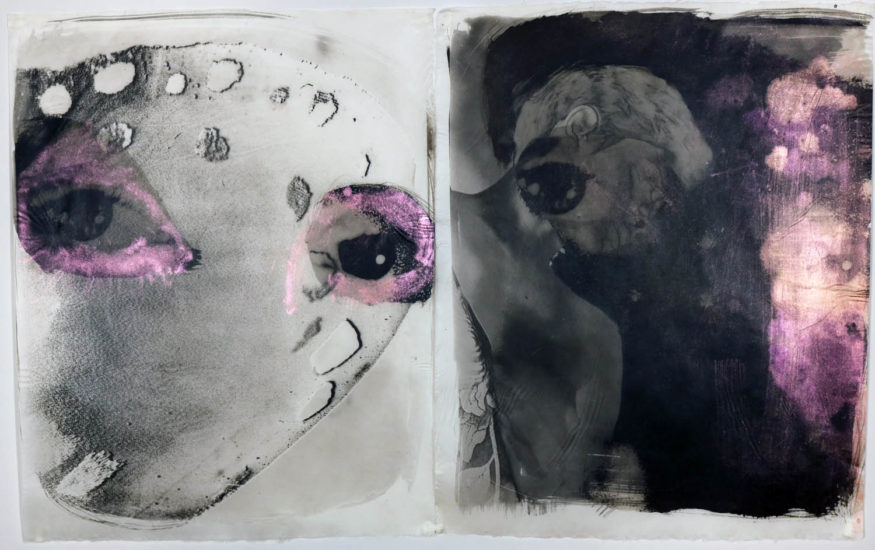

Through intuitively recombining and assembling images from photo negatives that I have made into new photographic surfaces in the dark room, I seek to explore these vital connections between organisms.

Tattoos As Gateways

Like a botanist collecting specimens, I am lured to making images culled from mythology, artifacts, naturalism, plants, animals, the ocean, human bodies, femininity, and especially tattoos. I see tattoos as gateways to merging our human experiences with the larger world of animals and plants. As light records a visual memory on a photographic surface that fades over time, tattoos mark the changing of time on evolving flesh.

Each of the negatives I make are exposed using sunlight onto a translucent paper, whose sensual, skin-like texture reminds me of the membranes that we share with all animate beings.

Process & Materials

Drawn to materials that illuminate our relationship to the earth, I make camera-less negatives in a traditional analogue darkroom, and photographs with a 4X5 inch large format camera.

I print both photographic types with the palladium process onto a Japanese gampi paper, which is handmade from the fibers of a wild plant, and is tactilely like silk. Palladium produces tonal distinctions of extreme subtlety, allowing even the darks to reflect light. It is an unforgiving medium. Once painted, it is not retractable and the paper substrate is permanently altered. With multiple printing, the deeply infused palladium tones work their way, layer by layer, into the gampi paper, much like a tattooer’s ink penetrates skin. Brushing the palladium as if drawing on the translucent, plant-based, handmade paper, and using the sun for exposure, brings spontaneity to each print.

Assembling multiple processes and materials in a single final work, I often layer my photographic negatives to make montages, and paint with pearl iridescent watercolors and add hand drawn markings atop the surfaces.

Photographic History

References to photographic history are central to my process. Palladium printing has been around since it was patented in the mid 1870s. Camera-less negatives harken back even earlier to the 1830s, with the pre-camera experiments of William Henry Fox Talbot, who described his process as ‘photogenic drawing.’ Like Talbot, I place flowers and leaves in my enlarger to allow their dynamic unfolding to ‘sketch’ their own portraits. Similar also to Anna Atkins, I experiment with different processes when working with plants.

Modern Artists

Artist and fashion photographer Irving Penn used platinum and palladium printing for his iconic portraits, still life works and his paintings. I use his techniques of double printing and also add painting to my works.

Furthering and complicating these photographic experiments in palladium, camera-less negatives, and sun prints, I create aggregates of many processes in the making of each final print.